My Story, My Connections: Shaun & Blue

Before Shaun and Blue could have a child, government officials wanted to ring up their ex-partners. Officials also interviewed their parents, conducted personality assessments and made both Shaun and Blue do a work experience stint with local children.

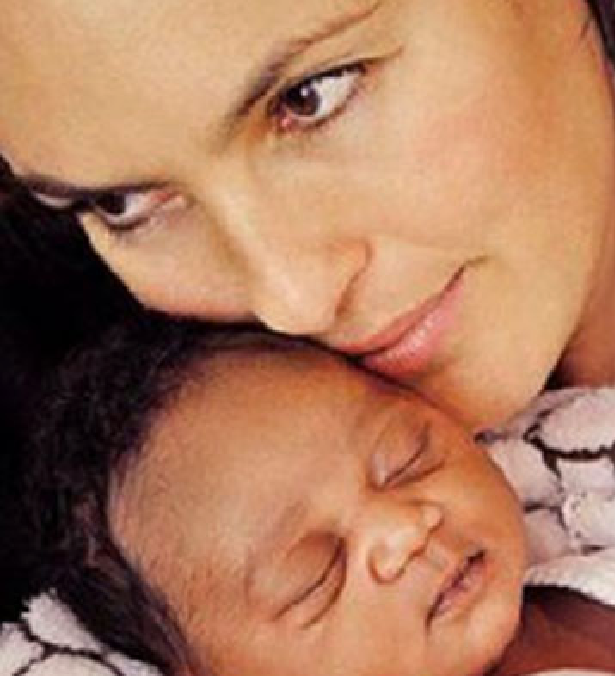

The couple passed every test with flying colours, and after a three-year battle earned the right to adopt a cute, baby boy – Joshi – who had spent the first 15 months of his life being shuffled between five different foster homes.

At first, Joshi “was very unsettled, with his primary attachment to food,” says Shaun. But the new parents put their careers on hold and invested hundreds of hours providing their baby with intensive care and support. Within a few years, they helped turn Joshi into a well-adjusted kid who now excels at primary school.

Their second adopted son, Dylan, proved an even greater challenge given the circumstances surrounding his birth. But again, patience and resilience won the day.

You can imagine their horror, when emigrating to South Australia, their new government told them they’re not recognised as a real family.

Shaun and Blue are a UK couple who started a family in England. They decided to move to Adelaide in search of a better lifestyle, and all seemed well at first when they were granted residency visas. But it was never going to be that easy.

“The day before we were due to fly out we received an email informing us our visas were suspended pending further checks. We were given no reason,” says Shaun.

With flight tickets bought and flat already leased, the family flew to Singapore, where they spent eight weeks in limbo before finally being allowed entry into Australia. Only later did they find out the nature of the problem.

“South Australian law doesn’t recognise same sex adoption,” say Shaun. Although eventually granted residency, he says “the state has more rights over our children than we do”.

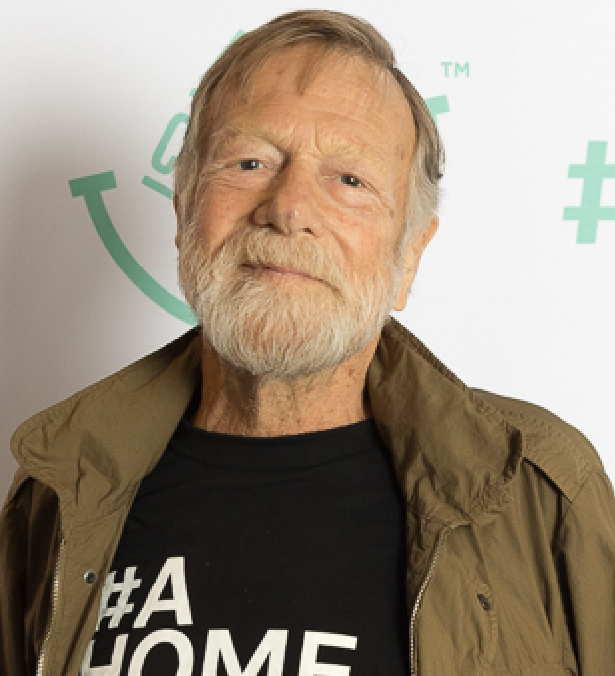

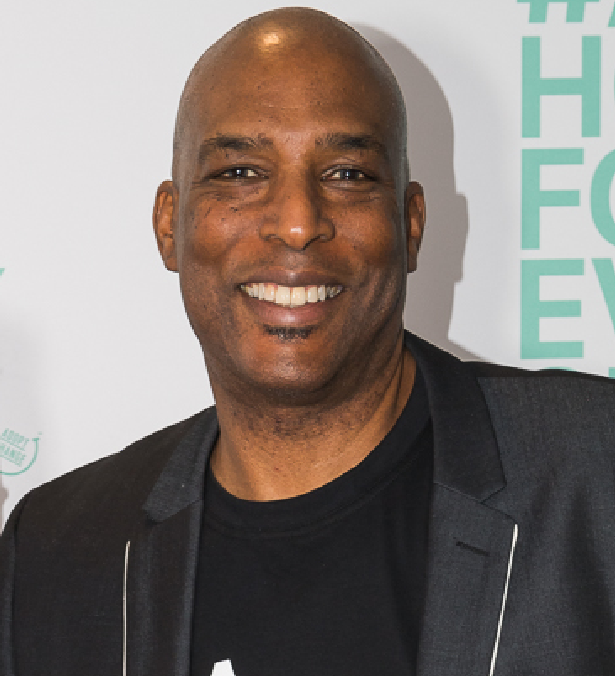

Shaun and Blue are now leading an advocacy campaign to legalise same sex adoption in South Australia. They’ve collected over 15,000 signatures in an online petition, and written to over 70 politicians.

“It’s odd, we’ve felt so welcome here. Even when taking the kids to monster truck rallies, nobody bats an eyelid,” says Blue, “there’s this real disconnect between what the people want and what policy makers do”.

The couple are touched by how supportive people have been, but also frustrated at the lack of understanding about adoption and non-traditional families. “When you’re with me, I’ll be your mother,” a teacher once told Joshi, not knowing how such sentiment can “mess up attachment,” says Blue.

Blue says educators here are generally not trained to understand the trauma history of adopted children, nor is there the “allocated budget” for post-adoption support that exists in the UK. He says this may be because adoption is so rare in the state.

Only three local children were adopted in South Australia last year – despite the fact over 1,300 kids have been in foster care for more than five years, unlikely to ever return home.

Blue says: “I work in mental health, so I’ve seen the toxic environments in which so many kids grow up. It’s unbelievable that adoption is not seen as a viable option here”. He gets emotional when he thinks about where his kids, now aged 6 and 4, might have ended up had they remained on the foster care treadmill. “I’ve heard of foster kids here being put up in hostels,” he says.

The South Australian government are yet to enact adoption law reform, but the couple are determined to keep fighting.

“We’ve been on this road for years and we are not getting off it,” says Shaun.