NSW inquiry to hear from children forced into motels, hotels due to shortage of foster carers

Original source: ABC News

Authors: Gavin Coote and Housnia Shams

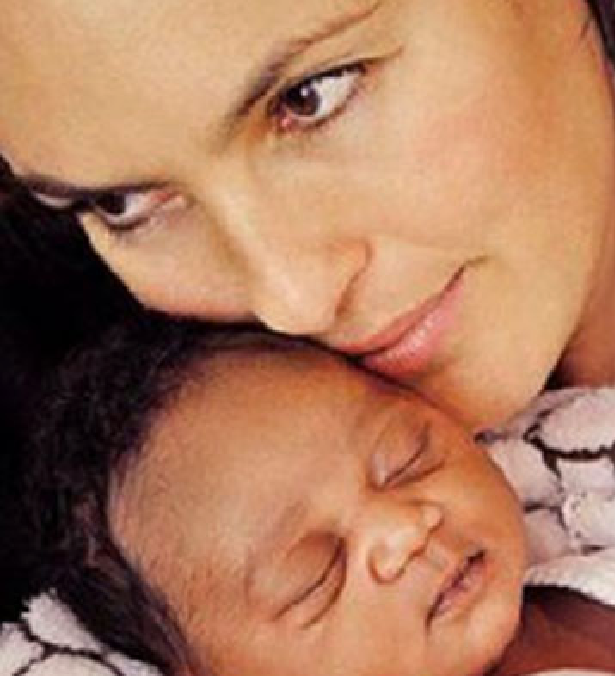

A special New South Wales inquiry will hear from vulnerable children who are living in hotels, motels and caravan parks due to an acute shortage of foster carers.

Key points:

- About about 120 people aged between 0-24 living in Alternative Care Arrangements

- These arrangements are costing the taxpayer about $100 million

- Sixteen reports of sexual abuse and 13 of physical abuse were recorded in just one month at these stays

There are about 120 people aged between 0-24 living in Alternative Care Arrangements (ACAs) due to a lack of residential options.

While such arrangements are designed to be short-term, some children are staying in hotels for more than a year, often supervised by untrained and unaccredited labour hire staff.

The ABC understands that in the 2022-23 financial year, ACAs cost taxpayers about $100 million, with 43 per cent of children reported as being at risk of significant harm.

In one month alone, there were 16 reports of sexual abuse and 13 reports of physical abuse.

Minister for Families and Communities Kate Washington said the inquiry, to be led by the Office of the NSW Advocate for Children and Young People, would shine a light on the problem.

“These arrangements with children going into hotels and motels in the absence of enough foster carers is costing an obscene amount of taxpayer money, but worse still, the outcomes are just terrible,” she said.

“As a government we are determined to reform the child protection system and our first priority is getting kids of out hotels and motels where so much damage is being done.”

Children and young people who are currently or have been in ACAs will give first-hand perspectives to the inquiry in closed hearings.

Staff in the child services sector are also expected to give evidence.

Renee Carter, the CEO of Adopt Change which runs a government-funded program in NSW to find and support foster carers, said it was crucial children’s experiences were the focus of any inquiry.

“Anything that’s not a home for family-based care is just not suitable for a child,” Ms Carter said.

“When children are removed from their parents due to it being deemed unsafe for them to be there, there’s a huge ethical obligation that government’s going to make sure they’re placed in an environment that’s safe and nurturing.

“And that’s not what it looks like if you put a child in a motel with a shift worker.”

Calls to overhaul ‘outdated’ system

Dr Lisa Griffiths, the Chief Executive Officer of child welfare organisation OzChild, which runs services for children in out-of-home care, said while there was a global shortage of foster carers, it was particularly acute in NSW.

“It has been an enduring problem, it’s been sluggish and hard for the numbers of children in alternative care arrangements to be reduced,” Dr Griffiths said.

“So it’s always encouraging to see a government say ‘enough’s enough’.”

Last week’s state budget included $200 million for the broader out-of-home care system, which supports about 15,000 children and young people.

Dr Griffiths said while there was no simple solution, more early intervention efforts were needed.

She said there should also be a greater focus on supporting and attracting foster carers — including more flexibility and leave arrangements for employees looking to juggle foster care and work.

“The foster care system hasn’t been revised for about two decades, it’s really quite outdated.”

Emma Maiden, general manager of advocacy and external relations at Uniting, said there needed to be more accredited transitional housing options for young people who couldn’t be placed in long-term residential care.

“We need to make sure that happens as little as possible,” Ms Maiden said.

“But when it is needed, there is a really good-quality option there that can be really looking out there for those young people and children.”

The final report from the inquiry is expected in February.