One in three kids removed from families become homeless

Original source: Newcastle Herald

Author: Gabriel Fowler

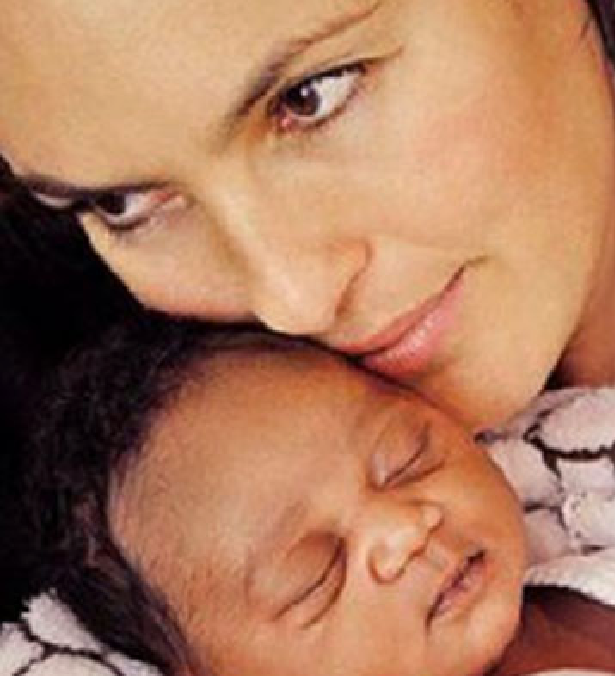

CHILDREN removed from their families, hundreds then holed up in hotels manned by shift workers, need homes and healing, Adopt Change says.

The national not-for-profit is calling on NSW Treasury to better provide for kids in out-of-home care with “adequate funding”.

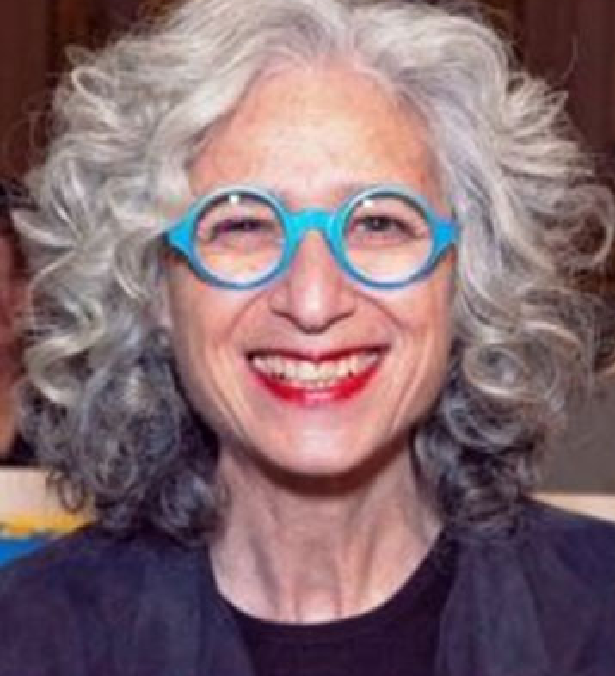

It is the NSW State Government’s responsibility to ensure they find a home with carer families who are supported, says Adopt Change CEO Renee Carter.

Commending the Minister for Communities and Families and Port Stephens MP Kate Washington for putting system reform on the agenda, Ms Carter said an immediate injection of funds is needed.

“Government takes a child from their birth family on the basis that they’re deemed unsafe,” Ms Carter said.

“They’re then under the parental responsibility of the minister, and then therefore the minister and the state have a huge obligation to ensure that the child is actually provided with what they’re taken into care for.

“They need to be given family-based alternative care, and they need to be given the support to heal. We are calling for government to commit to a home and healing for every child because that’s the fundamental premise of bringing a child into the care system.

“Unfortunately, what’s happening now, and what has been happening for a while is that a child is brought into the care system and for a myriad of reasons, they’re not actually being put in home-based care, or even if they are, they’re not being given stability or permanency.”

The outcomes are tragic, Ms Carter said, with a third of young people ending up homeless after the first year of leaving care at 18, and 75 per cent not finishing school

Ms Washington said she was shocked when she came into office to learn how many children were living in what’s known as ‘alternative care arrangements’ which include hotels and motels.

“Under the former government, the use of hotels and motels for vulnerable children skyrocketed, and the child protection system was left to spiral out of control,” Ms Washington said.

The number of children living in those placements has dropped by 42 per cent from 139 children in November, to 80 in February, she said.

At a Budget Estimates hearing on March 4, Ms Washington said some of those children had been restored safely to their families, some were now in foster homes, and some had beene placed into residential care with therapeutic support.

Ms Carter said it was costing the government an average of $840,000 to keep a child in an emergency placement only to deliver terrible outcomes, compared to the support that a carer provides on just $15,000 a year.

Former Homelessness NSW CEO Trina Jones has been appointed as the state’s first rent commissioner to advise the government on addressing the growing rental crisis.

“The money is going into the wrong place,” Ms Carter said.

“It’s not a particularly viable role in this economic climate either. We could double our program if we had the money from four of those placements.

“We could assist in locating over 1,100 additional potential homes and provide support on 2,250 additional carer support cases to retain carers. So it is really significant.”

In NSW, Adopt Change operates the government-funded My Forever Family NSW program to support, recruit, train and advocate for foster and kinship carers, guardians, and adoptive parents from out-of-home care.

In its pre-budget submission to Treasury, Adopt Change has called for a review and analysis of supports currently offered to carers of children in out-of-home care.

“We have requested funding for one year to put together a task force and provide recommendations on two key things,” Ms Carter said.

“One is what should carers actually be given to make it a viable role, because $15,000 is not enough.”

The second priority was for therapeutic care funding to be individualised and attached to each child, rather than flowing into agencies’ pooled funds.