SBS News: For Brad, adoption meant a ‘sense of belonging’. So why are so few Australians doing it?

Author: David Aidone

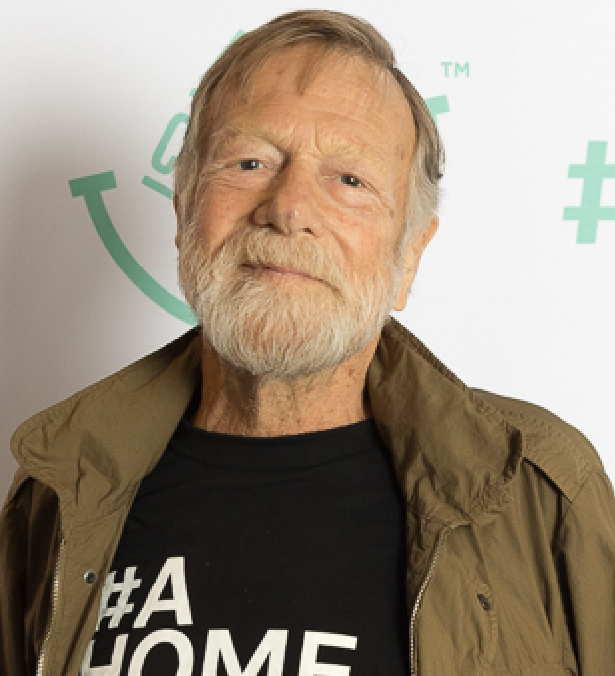

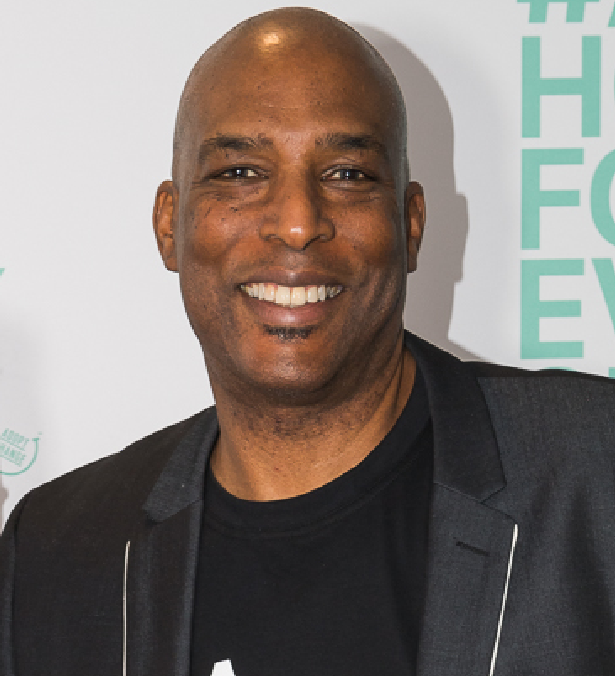

Being adopted ended a “long and challenging” chapter of former AFL player Brad Murphy’s life. Advocates say adoption is not always suitable, but they’re concerned numbers have hit a record low.

With a mother battling drug addiction and a father in prison, Brad Murphy was placed into foster care when he was just 16 months old.

Mr Murphy, a former AFL player turned adoption advocate, said he was among the “fortunate” ones, having stayed with one family until he was 18 years old.

It was the kind of stability that some children in out-of-home care don’t experience. Adopt Change, an adoption advocacy group, says some children can move around the care system many times.

Mr Murphy, 38, said his carers wanted to adopt him, but it was not possible because one of his parents would not consent.

He said this meant he “missed out on a bit of childhood”.

“You had to apply to go on school camps or excursions,” he said, explaining that this required forms to be sent to his case manager and then to the relevant state government department for approval.

“So sometimes I missed out on the little things that we probably take for granted now … because documentation wasn’t signed and delivered.”

Those carers became his adoptive parents after he signed the necessary paperwork when he turned 18.

“It was a really happy time and I finally felt like I belonged to a family,” Mr Murphy said. “To some, it might just be a piece of paper, but to me, it was a full stop to the end of a pretty long and challenging period.”

Mr Murphy and Adopt Change say that adoption is not suitable in all cases, but they are concerned that Australian adoption figures have hit a record low.

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s (AIHW) latest data release on Friday showed 208 adoptions nationally in 2021-22, made up of 192 domestic and 16 overseas adoptions.

The total adoption figure is the lowest since records began in the late 1960s. The domestic figure, while not the lowest it has ever been, has fallen for the last two years.

Of 192 domestic adoptions, 161 were by those who had a pre-existing relationship with the child, such as a foster carer.

The most recent child protection figures, released by AIHW in June last year, showed there were about 46,000 children living in out-of-home care as of 30 June 2021.

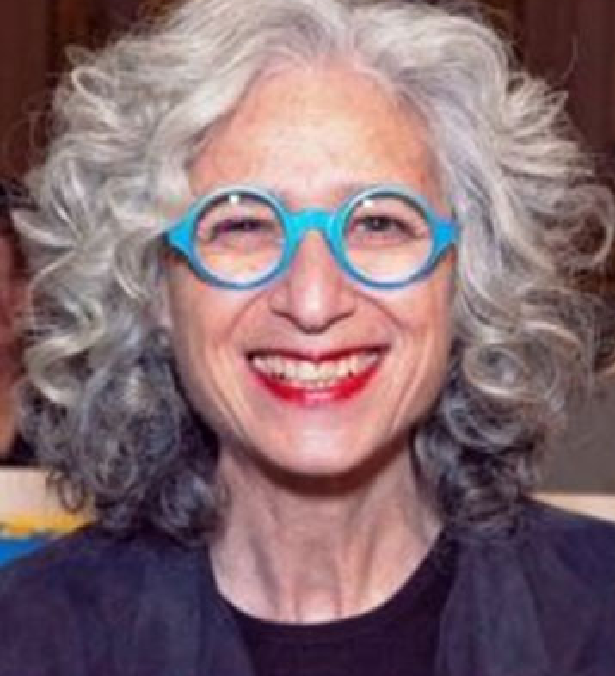

Renée Carter, CEO of Adopt Change, said the ideal situation was for children to return to their parents but for some that wasn’t possible.

“Of those 46,000, most of them will stay in the care system and some will move around a lot,” she said.

Australia has a history of “problematic adoptions”, according to Damian Riggs, a professor at Flinders University’s College of Education, Psychology, and Social Work.

“We’ve had three different inquiries: the forced adoption of children from the UK to Australia, the forced adoptions of First Nations children, and the forced adoptions of children typically born in Australia to unwed mothers,” Professor Riggs said.

“I think that resulted in … a swing towards trying to reunify children with their birth parents, or use foster care, or other means that did not extinguish parental rights,” he said.

Professor Riggs described the adoption figures as a “red herring” because most Australian jurisdictions had forms of permanent care that often gave carers similar rights to adoptive parents.

“Adoption tends to be reserved for parents who willingly place their children for adoption, which happens in very small numbers, or children where parents die and there’s no next of kin,” he said.

“So I think that’s why adoption numbers are so small — because there are other routes to permanency that people pursue.”

Ms Carter said permanent care orders, which remain in force until the child is 18, had increased “somewhat”.

“But we’re still only talking thousands,” she said. “Adoption goes one step further than that and provides them (children) legal stability for life.”

Ms Carter supports the NSW model, which she described as permanent care-centric, and said she would like to see it adopted more widely.

“The legislation was tailored to make sure that within two years a permanency outcome was determined for the child,” she said.

“So if a child can’t return home, they can be placed under the guardianship of a relative or adopted by a foster family that is suitable for them.”