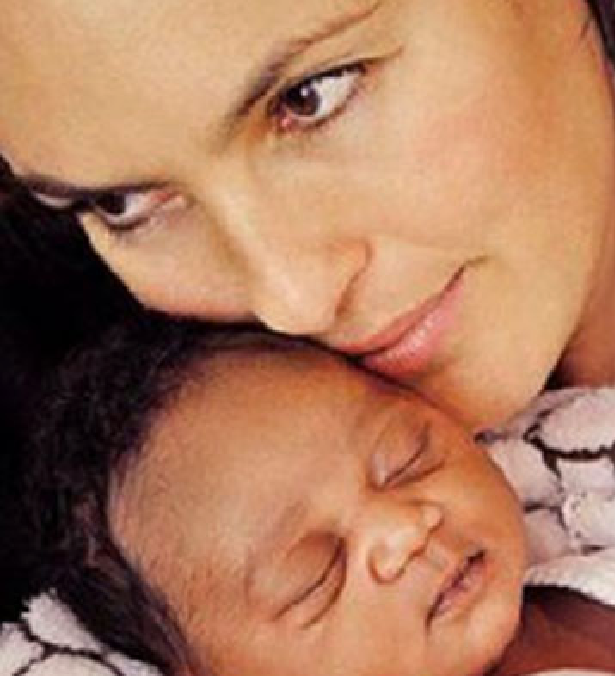

We have guardianship, it is not enough

Andy and her partner, Joss, have a foster daughter, Ruby, who is eight years old*. She has been in this placement since she was three months of age. Ruby does not have contact with either of her birth parents despite contact being actively and repeatedly sought by Andy and Joss. Until she was about five years of age Ruby was very settled and happy in her family. She knew that she had two families but felt very secure in her foster placement. However, at age five, there was a big change as Andy and Joss began the process of obtaining guardianship for Ruby, and as Ruby started school.

The process of obtaining guardianship had a very negative impact on Ruby. It increased the amount of contact that Ruby had with agency workers and not all interactions were managed appropriately. During one private interview, it was somehow communicated that the agency had the power to move Ruby from her current foster home. This had a devastating impact upon Ruby and she became terrified that strangers had power over her life and that she might lose her parents and home. She also became sensitive to her status as a foster child.

Starting school exacerbated Ruby’s insecurities as the school treated her family differently and stigmatised Ruby. When speaking to Ruby, school staff persisted in referring to her parents as Andy and Joss or as her guardians rather than her mums. School staff felt able to initiate discussions with Ruby about her birth family and history and dismissed Andy and Joss’ concerns because they did not see them as having the status of parents. The difference between Ruby’s surname and that of her parents was very evident in the school context and distressed her greatly. The awareness of Ruby’s status as a foster child resulted in other pupils teasing Ruby about being a foster child and not having real parents. As a result of these challenges, Ruby developed severe anxiety that has required ongoing medical and psychological treatment.

Andy and Joss obtained guardianship for Ruby and they have done everything possible to help Ruby to feel secure. They advocated within the hierarchy of the Department of Education to force school staff to stop telling Ruby they were her guardians rather than her parents. They legally changed their surname so that it was the same as Ruby’s. They provided her with constant reassurance of their love and commitment to her. However, Ruby remains aware that she is not fully their child and has repeatedly asked to be adopted.

Guardianship has provided Ruby’s parents with the ability to make decisions for her but it has not addressed society’s attitudes or understanding of what constitutes a family. It is evident that society recognises adoption but it doesn’t recognise guardians as full parents. As a result, Andy and Joss’ commitment to Ruby is somehow up for discussion or individuals feel paternalistic towards Ruby as a child of the State and that they have a right to information about and input into her life. Andy and Joss say that it is the little, everyday events that undermine Ruby’s belonging. It’s the interactions with medical staff and members of the public who question their relationship to each other and ask inappropriate questions. It’s the kids at school who tell her that she doesn’t really belong to her parents.

Andy and Joss had thought that guardianship would provide Ruby with the belonging that she needed. However, they now wish that they had persisted in advocating for adoption. Their reasons for wanting adoption are solely concerned with Ruby’s feelings and needs. Andy and Joss don’t want to take anything away from Ruby or her birth parents and they hope that Ruby will have more contact with her birth family in the future. They just want adoption so Ruby has full legal belonging in their family and so she can really feel safe.

* Identifying details have been amended to allow for privacy of those involved